Technical Memorandum

DATE: February 18, 2016

TO: Boston Region MPO

FROM: Chen-Yuan Wang, MPO Staff

RE: Summer Street/George Washington Boulevard Subregional Priority Roadway Study in Hingham and Hull

The roadway corridor of Summer Street, Rockland Street, and George Washington Boulevard in Hingham and Hull was selected for analysis in a Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) funded project for federal fiscal year (FFY) 2015: “Addressing Safety, Mobility, and Access on Subregional Priority Roadways.” The work program for this corridor was approved on October 16, 2014, and the selection was approved on April 2, 2015.

This memorandum summarizes the existing conditions and issues, roadway operations and safety analyses, and proposed short- and long-term improvements for the entire study corridor and for specific locations. It contains the following sections:

This memorandum also includes technical appendices that contain the data and methods used in the study.

During the MPO’s outreach for developing the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP) and the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) subregional groups and other entities submit comments and identify transportation problems and issues that concern them. These issues are related to bicycle, pedestrian, and freight accommodation, bottlenecks, safety, or lack of safe or convenient access for abutters along roadway corridors. They can affect not only mobility and safety along a roadway and its side streets, but also quality of life, including economic development and air quality.

The purpose of this study was to identify roadway corridors in the MPO region that are of concern to Boston Region MPO subregional groups, but which have not been identified in the LRTP regional needs assessment. In addition to identifying the problems, this study also recommends improvements to address them. In addition to mobility, safety, and access, the study considered transit feasibility, truck issues, bicycle and pedestrian transportation, preservation, and other topics.

This corridor was selected through a comprehensive process. First, MPO staff identified potential study locations using various sources: soliciting suggestions during the outreach process for the FFY 2015 UPWP; reviewing meeting records from the UPWP outreach process for the past five years; and appraising potential locations from the monitored roadways in the MPO’s Congestion Management Process (CMP) program.

MPO staff identified 30 roadway corridors in the MPO region as potential study locations. The staff assembled detailed data on the identified roadways and evaluated them according to four selection criteria1:

The Summer Street/George Washington Boulevard corridor contains several high-crash and congested locations, such as the Route 3A and North Street intersection, which need to be improved for the safety and mobility of users of all modes. Major portions of the corridor have strong potential for design and implementation toward a Complete Street2 roadway. More importantly, the study site has strong support from all stakeholders, including officers and representatives from Hingham and Hull and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT).

The objectives of this study were to:

This study focuses on an almost three-mile corridor that consists of Summer Street (from North Street to Rockland Street), Rockland Street (from Summer Street to George Washington Boulevard), and the entire section George Washington Boulevard in Hingham and Hull. All segments of the corridors are under the jurisdiction of MassDOT Highway Division District 5.

Based on MPO staff requests, MassDOT collected extensive traffic volumes, spot speed data, and intersection turning-movement counts (including pedestrian and bicycle movements and the percentages of heavy vehicles) for this study. The data were collected during two periods: late spring (June 1-4, 2015), and high summer (July 9-12, 2015). Staff also collected various data from the towns, including recent transportation and land-use studies, information about adjacent developments, and multiple-year police crash reports.

During the course of the study, MPO staff worked closely with the towns and MassDOT District 5. Two advisory meetings were held to guide and support the study. The advisory members included representatives from Hingham and Hull, State Senator Hedlund’s and Representative Bradley’s offices, MassDOT, and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (see Appendix A for a list of meeting participants).

In the first meeting (May 13, 2015), MPO staff introduced the study, received input about the corridor’s issues and concerns, and coordinated data collection. In the second meeting (November 3, 2015), MPO staff reviewed the findings and proposed improvement alternatives. After the meetings, staff continued to receive comments from the advisory members and revised the proposals accordingly.

This section examines the corridor’s location, associated major transportation facilities, transit services, existing roadway configurations, and adjacent land uses. It also summarizes the concerns raised in the first advisory meeting.

As seen in Figure 1, the study corridor is located in the coastal areas of Hingham and Hull, approximately 15 miles from Boston Downtown. It runs along the south side of Hingham Bay from Hingham Harbor, across Weir River, to Nantasket Beach.

The corridor is the major roadway used by residents of Hull and North Hingham to access Boston proper and adjacent communities. It consists of three segments: Summer Street (from North Street to Rockland Street), Rockland Street (from Summer Street to George Washington Boulevard), and George Washington Boulevard (the entire section in Hingham and Hull).

The section of Summer Street from North Street to the Route 3A Rotary is part of State Route 3A. It is classified as an urban principal arterial and is the busiest section of the corridor. The other sections of the corridor all are classified as urban minor arterials and carry less traffic than the Route 3A section.

Major cross streets of the corridor include North Street, Water Street, Chief Justice Cushing Highway, Summer Street, and Rockland Street in Hingham; and Rockland Circle, Wharf Avenue, and Nantasket Avenue in Hull. Most of these cross streets are urban minor arterials, except Summer Street and Rockland Circle (both classified as collector roads).

Essentially, the corridor is a four-lane roadway, with two travel lanes in each direction. The adjacent land uses are mainly residential and public open space, with some businesses in the Hingham Harbor area. Sidewalks exist mainly on the north side of the corridor, except in the Harbor area, where sidewalks also exist on the south side. There are no dedicated or separated bicycle lanes in the corridor. A multi-use trail exists on the north side of the corridor in Hingham from Martins Lane to the Hull border. The trial is about six- to-eight-feet wide and operates in both directions.

In addition to the roadway network, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) Greenbush commuter rail line runs south of the corridor parallel to Summer Street and Rockland Street. This and other transit services are described further in the next section.

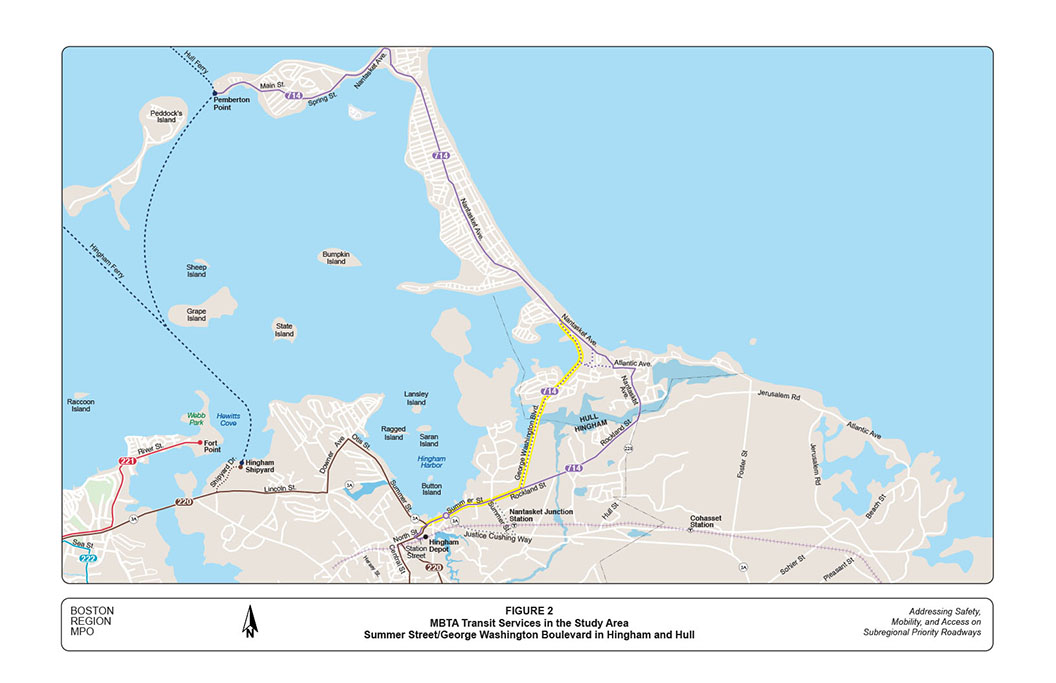

The MBTA provides a number of transit services in the study area, including the Greenbush commuter rail line, Bus Routes 220 and 714, and Hingham and Hull Ferries (See Figure 2.)

The Greenbush line runs between South Station in Boston and Greenbush Station in Situate—through Quincy, East Braintree, Weymouth, Hingham, and Cohasset—and makes two stops in Hingham: West Hingham and Nantasket Junction. Nantasket Junction station is located on Summer Street near Route 3A (Chief Justice Cushing Highway) approximately 1,000 feet south of the study corridor. The station has 495 parking spaces, which are about 20-to-30 percent occupied during weekdays, with a lower occupancy rate on weekends.

Route 220 runs between Quincy Center Station (MBTA rapid transit Red Line) and Hingham Depot, with a relative high frequency of more than 40 weekday trips each way.3 On Saturdays, it maintains approximately 30 trips each way, and on Sundays about 15 trips each way. It connects to Route 714 at Hingham Depot for various destinations in Hull, including Nantasket Beach and Hull Medical Center (on George Washington Boulevard).

Route 714 runs between Hingham Depot and Pemberton Point Ferry Station in Hull. It travels mainly on Nantasket Avenue and partly through the study corridor, with diversions to Nantasket Junction by request only. It provides 14 trips each way on weekdays and 9 trips each way on weekends. This service operates under contract, and uses smaller vehicles than the regular MBTA buses.

The MBTA ferry service consists of two major routes: Hingham-Boston and Hingham-Hull-Boston, via Logan Airport. The service is operated by Boston Harbor Cruises, and utilizes various vessels each with the capacity for about 350-to-400 passengers.

The Hingham-Boston route provides 18 round trips daily from Hingham (Hewitt’s Cove/Hingham Shipyard Terminal) to Boston (Rowe’s Wharf). The Hingham-Hull-Boston route provides 18-to-20 round trips daily from Hingham or Hull (Pemberton Point Terminal) to Boston (Long Wharf), with various arrangements of stops at Pemberton Point, Logan Airport, Grape Island, and George’s Island. These trips include eight inbound stopovers/origins from Hull and 12 outbound stopovers/destinations to Hull.4

During weekends, the service provides 16 Saturday and 14 Sunday round trips from Hingham to Boston, with six inbound and four outbound trips stopping over at Pemberton Point in Hull and Logan Airport; the other trips stop over at Grape, George’s and other Boston Harbor Islands. The weekend ferries, along with stopovers at the Boston Harbor Islands, usually end on Columbus Day weekend.

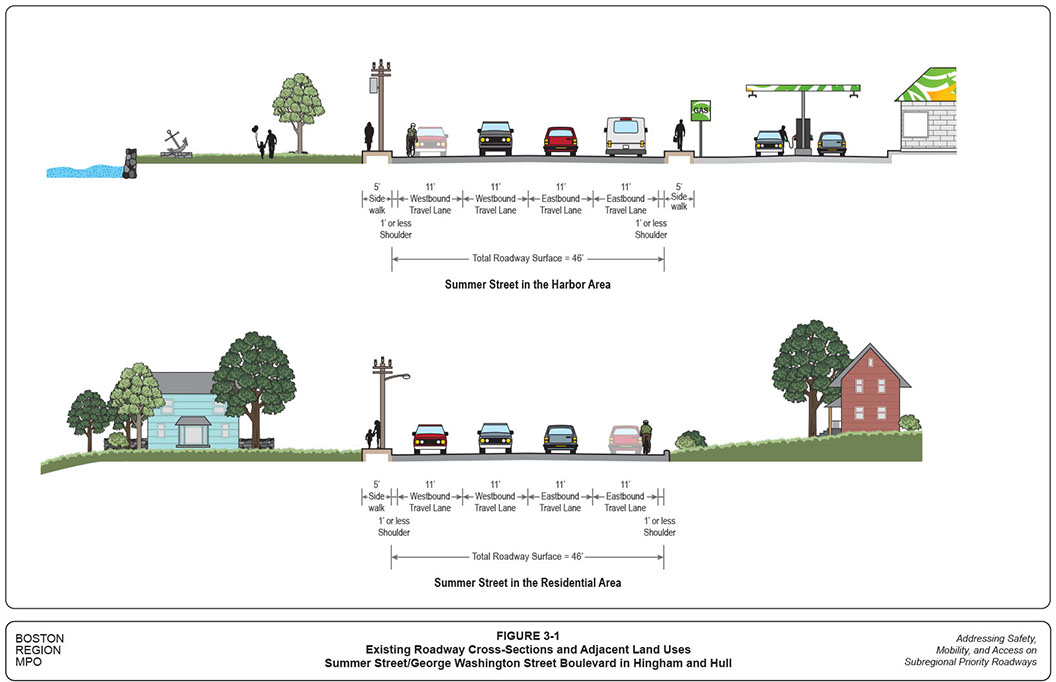

The study corridor has a consistent four-lane layout, but with quite different adjacent land uses and roadside conditions, as analyzed below.

Summer Street from North Street to Route 3A Rotary is the busiest section of the corridor. In addition to local traffic, it carries regional traffic from Chief Justice Cushing Highway and North Street.

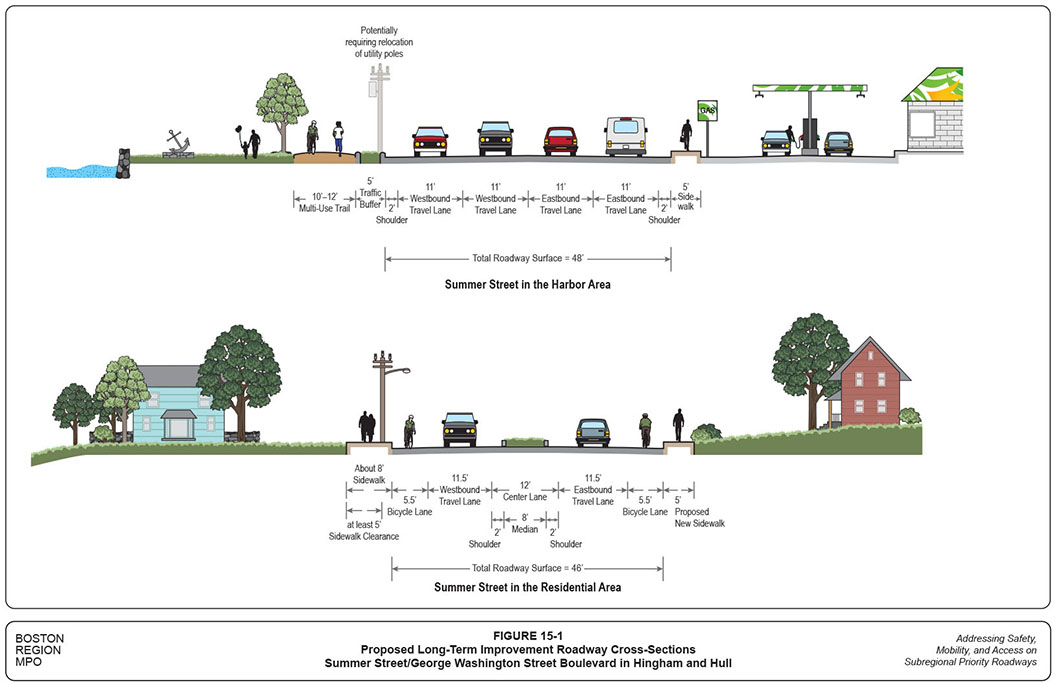

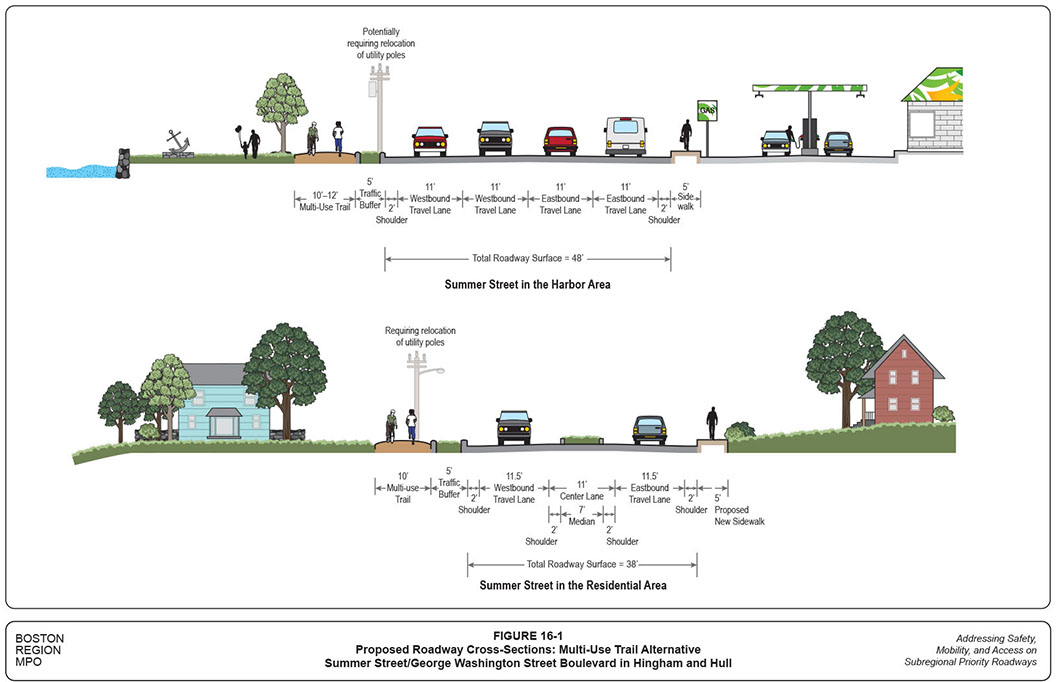

The top graphic in Figure 3-1 shows Summer Street’s existing roadway conditions and adjacent land uses. The cross-section is based on the street view of an eastbound driver. The roadway surface consists of four 11-foot travel lanes. With almost no shoulders on both sides, the travel lanes contain catch basins, and bicycles need to travel with the traffic.

Summer Street has five-foot-wide sidewalks on both sides, which frequently are blocked by utility poles. Pedestrian access from the downtown side to the harbor side is limited and difficult. Crosswalks exist only at the North Street intersection; and the east-side crosswalk is hard to access because of fast and heavy right-turning traffic. There are no crosswalks at the rotary; its wide layout, with fast, heavy traffic, makes it difficult for pedestrians and cyclists to access the harbor side.

Hingham Harbor occupies the roadway’s north side with mainly public open spaces (Whitney Park and Veterans Memorial Park), and a few private developments, including a private wharf (Hingham Harbor Marina), a coffee shop, and a small office building near the rotary. A number of business developments, including restaurants, a bank, a supermarket, gas stations, and a car wash occupy the south side. This area is regarded as an extension of Downtown Hingham (also known as Hingham Square), which consists of businesses, shops, and restaurants that are thickly settled along North Street.

The bottom graphic of Figure 3-1 shows the existing roadway conditions and adjacent land uses on Summer Street in the resident area of Hingham. The similar four-lane roadway layout extends from the harbor area to the residential section, with five-foot sidewalks on only the north side, which frequently are blocked by utility poles. The adjacent land use is predominantly single-family houses on relatively large tracts.

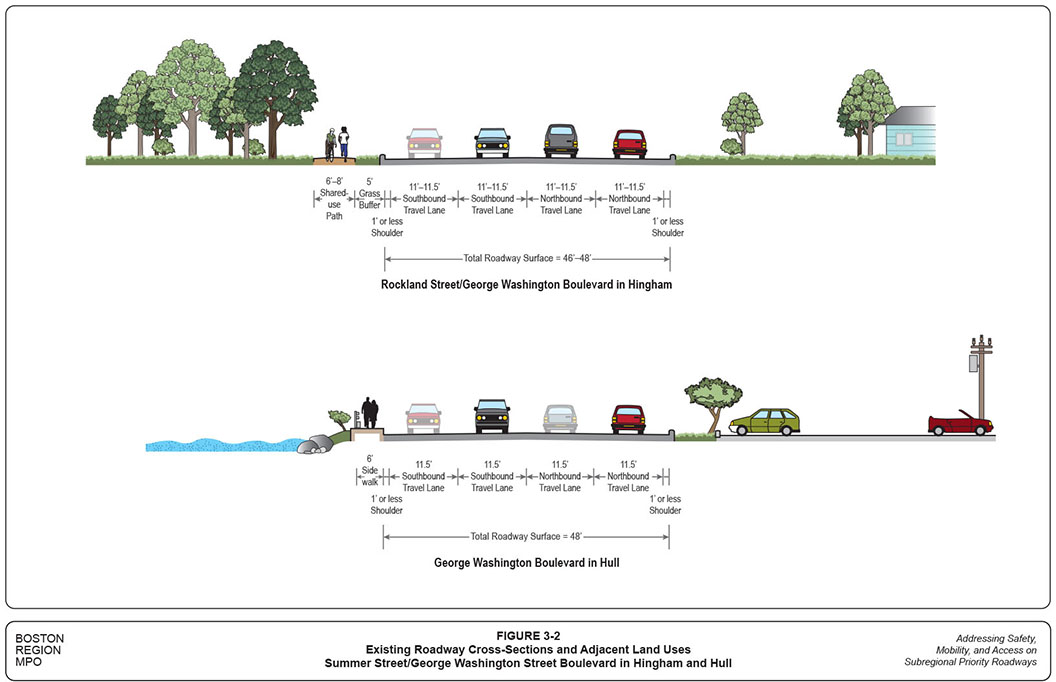

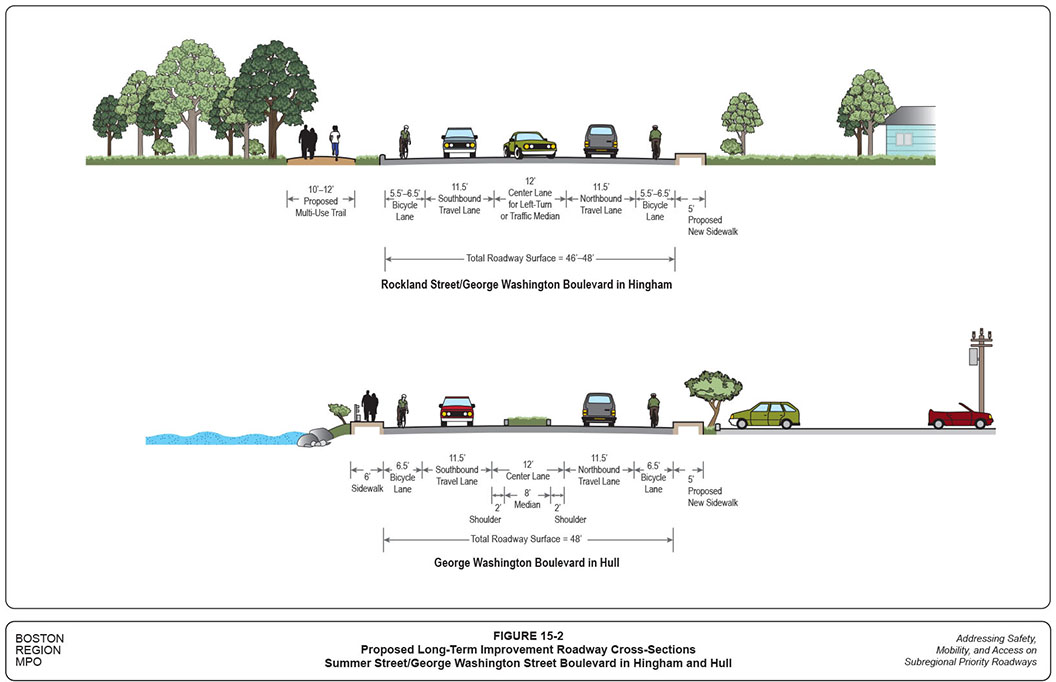

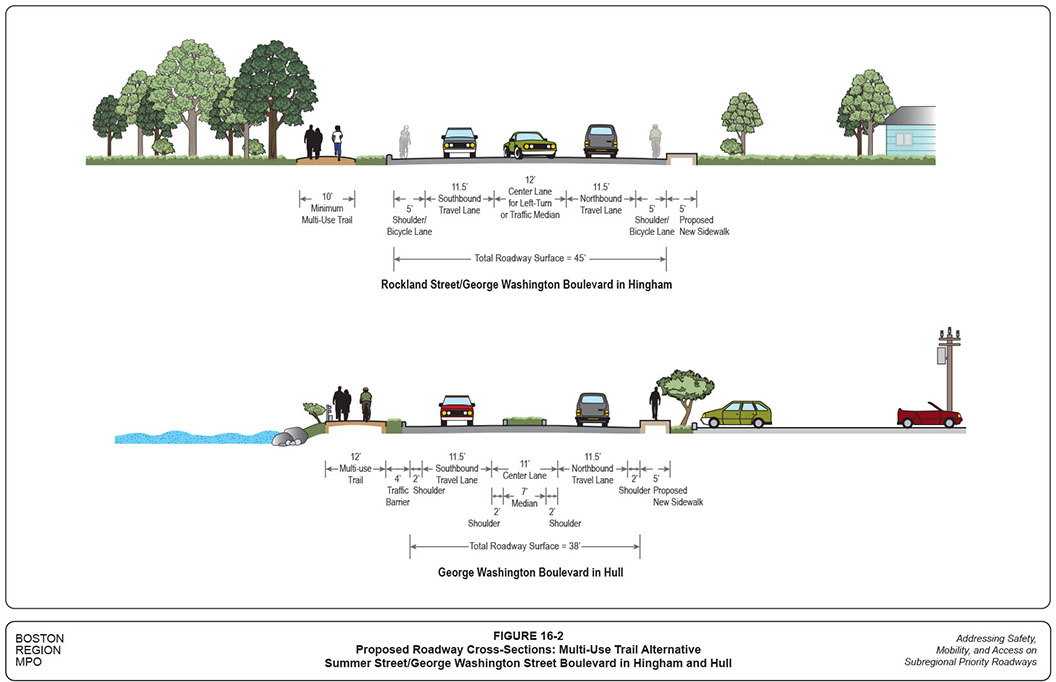

The top graphic of Figure 3-2 shows the existing roadway conditions and adjacent land uses on Rockland Street and George Washington Boulevard. Rockland Street has the same four-lane layout as Summer Street: 11-foot lanes with narrow shoulders. The roadway gradually widens to include four 11.5-foot lanes on George Washington Boulevard, and the adjacent land areas gradually become more open.

In this section of the study area, the north-side sidewalks are replaced by a multi-use six- to-eight-foot-wide trail, which runs from Martins Lane to the bridge over the Weir River. A grassy, five-foot-wide buffer generally exists between the trail and the roadway. Though its size is considered substandard, this trail provides a much safer accommodation for pedestrians and cyclists than do other sections of the corridor.5

The land use on the north side generally consists of open spaces, including a large section of parkland owned by the town, and some private vacant land parcels. On the south side, the land use is mostly single-family residential, except for a major section of George Washington Boulevard occupied by Hingham District Court.

The bottom graphic of Figure 3-2 shows the existing roadway conditions and adjacent land uses on George Washington Boulevard in Hull. The layout is the same as that of George Washington Boulevard in Hingham: four 11.5-foot travel lanes with narrow shoulders. The north-side multi-use trails are replaced by six-foot sidewalks with no traffic buffers. They are suitable for pedestrians, but and not for bicyclists. Bicycles going to Nantasket Beach need to travel with the traffic.

The adjacent land on the north side is mainly coastal areas, including a single-family home neighborhood, community health care center, and the Steamboat Wharf commercial development. On the south side, south of Rockland Circle is the Weir River estuary with a commercial development, a multi-family home building, and a few single-family homes; north of Rockland Circle are the remote parking lots of Nantasket Beach with a few commercial developments near the roadway’s intersection with Nantasket Avenue.

The northern part of this corridor section is adjacent to Nantasket Beach, a popular destination for beachgoers, walkers, joggers, and others coming to enjoy the ocean view. The beach, owned by the Department of Conservation and Recreation, is 1.3 miles long with nearly 1,500 parking spaces. During the summer, pedestrian and bicycle activities abound near the beach, especially on weekends. Hull is concerned with the high volume of traffic around Nantasket Beach, which causes congestion, as well as the lack of convenient transit service and safe bicycle accommodations to the beach.

In the first study advisory meeting, representatives from the towns and MassDOT shared their views about the corridor, which general concerns are summarized below:

The advisory members also discussed concerns about specific locations in the corridor, where analyses identified safety and operational problems, which along with the proposed improvements, are summarized by location in Section 5 of this memo.

This section examines the corridor’s traffic volumes and patterns, pedestrian and bicycle volumes, traffic operations at major intersections, and travel speeds at various locations. To support these analyses, MassDOT collected various transportation data, including daily traffic volumes, spot speed data, and intersection traffic, pedestrian, and bicycle counts during two periods: June 1-4, 2015 and July 9-12, 2015, one representing average daily traffic conditions and one representing high-summer Saturday traffic conditions.

The most fundamental data for analyzing traffic intensity and patterns in a roadway corridor are daily traffic volumes. MassDOT collected traffic volumes at 12 locations: seven in the corridor and five on adjacent streets.

Figure 4 shows daily traffic volumes at the twelve locations based on Automatic Traffic Recorder (ATR) counts collected in the weekday period of June 1 to 4. The numbers in the graphic represent average daily directional volumes. The two tables in the graphic further summarize the data by count locations, directional split, combined volume of both directions, and adjusted annual average daily traffic (AADT).

In general, the June counts show that traffic in the corridor is split evenly, by approximately 50 percent in each direction. Total traffic volumes vary significantly among different locations in the corridor, ranging from approximately 13,000 vehicles per day (near Nantasket Avenue) to nearly 30,000 vehicles per day (west of Route 3A Rotary).

In June, traffic in this area is somewhat higher than the annual average volume. Adjusted by the seasonal factors, AADT data indicate that the corridor carries traffic volumes of different magnitude, from 11,500 vehicles near Nantasket Avenue to 26,500 vehicles west of Route 3A Rotary on an average day. Overall, traffic volumes gradually become less going from the western to the eastern segments of the corridor.

Figure 5 shows the average daily traffic volumes at the same 12 locations based on ATR counts collected during the weekend of July 9 to 12. The numbers in the graphic represent the highest level of daily directional volumes in that period—Saturday, July 11, 2015. The two tables in the graphic further summarize the data by location, directional split, and combined volume of both directions.

Similar to the weekday counts, the Saturday counts show that the corridor carries evenly split traffic on summer weekend days. Total traffic volumes vary among different locations, ranging from almost 22,000 vehicles per day on George Washington Boulevard near Nantasket Beach to 38,000 vehicles on Summer Street in the Hingham Harbor area. This accounts for an approximate 45-to-85 percent increase from the normal weekday traffic, mainly because of the traffic in and around Nantasket Beach in Hull.

Saturday, July 11, 2015, was dry, with a temperature of more than 85 degrees. These traffic counts represent almost the highest potential traffic volumes in the corridor under the conditions cited above, which presumably would occur approximately four-to-six weekends every year. The Saturday traffic volumes at the various locations are summarized below:

In addition to daily traffic counts, MassDOT collected turning movement counts at major intersections in the study corridor, including vehicle movements (by vehicle types), bicycle movements, and pedestrian crossings. They were collected during the morning peak period (7:00–9:00 AM) and the evening peak period (4:00–6:00 PM) on Thursday June 4, 2015, and during the midday peak period (10:00 AM–2:00 PM) on Saturday July 11, 2015. Staff then identified the peak hour in each of the peak periods for various traffic operational analyses.

Figure 6 shows the weekday peak-hour traffic and pedestrian volumes at major intersections in the corridor. Entry volumes at these intersections vary from 1,000 vehicles per hour at the intersection of George Washington Boulevard at Wharf Avenue to 2,600 vehicles per hour at Route 3A Rotary, and generally are somewhat higher in the evening than in the morning.

The three intersections in the Hingham Harbor area had higher traffic entry volumes than did the other intersections, each carrying approximately 2,500-to-2,600 vehicles per peak hour. The two intersections in the Hingham residential area carried approximately 1,400-to-1,600 vehicles per peak hour each. The intersections on George Washington Boulevard carried approximately 1,000-to-1,300 vehicles per peak hour each.

Four pedestrians in the AM peak hour and ten pedestrians in the PM peak hour crossed the intersection of Summer Street at North Street. Thirty-three (33) pedestrians in the AM peak hour and 23 pedestrians in the PM peak hour crossed the intersection of George Washington Boulevard at Nantasket Avenue. The other intersections generally experienced five or fewer pedestrian crossings per peak hour.

Figure 7 shows the summer Saturday peak-hour traffic and pedestrian volumes at major intersections in the corridor. These intersections generally carried a total entry volume that was approximately 20 percent to 75 percent greater than during the June weekday peak hour.

The three intersections in Hingham Harbor carried between 3,000-to-3,200 vehicles per peak hour each. The two intersections in the Hingham residential area carried approximately 2,300-to-2,400 vehicles per peak hour each. The two intersections on George Washington Boulevard leading to Nantasket Beach carried approximately 2,000-to-2,100 vehicles per peak hour each.

Noticeably, the Saturday count showed that pedestrian activities were significant on the roadways in the Hingham Harbor and Nantasket Beach areas. The intersection of Summer Street at North Street had 74 pedestrian crossings during the midday per peak hour from 12:00 to 1:00. The intersection of George Washington Boulevard at Nantasket Avenue had 102 pedestrian crossings during the midday peak hour. The intersection of George Washington Boulevard at Bay Street/Nantasket Avenue had 51 pedestrian crossings during the midday peak hour.

The turning movement counts at major intersections indicate that three or fewer bicycles traveled the corridor on a spring weekday (June 4, 2015). However, the cycling activity increased significantly during summer weekends.

The Saturday (July 11, 2015) counts show that there were between 20 and 30 bicycles traveling in the corridor during the four-hour period from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM, and among them approximately 10-to-12 bicycles traveling in the peak hour from 10:00 to 11:00 AM. Figure 8 shows the estimated bicycle volumes by direction at various locations in the corridor, excluding bicycles that traveled on the multi-use path.

The adjacent areas of the corridor contain scenic coasts, wetlands, and woodlands. Presumably, bicycle volumes would be much higher if the corridor contained dedicated bicycle lanes.

It is essential to examine the amount of heavy-vehicle traffic in a study corridor, as an unusually high percentage of heavy vehicles (trucks and buses) may seriously affect roadway operations. The weekday turning movement counts by vehicle type indicate that, on average, most intersections in the study corridor carried about two percent of heavy vehicles during peak-hour traffic; and a few carried about three percent in the morning peak hour, and one percent in the evening peak hour. These percentages are considered normal, or even slightly less than average, and would not seriously affect roadway operations.

Based on the turning movement counts, MPO staff constructed peak-hour traffic models for the entire corridor and conducted capacity analyses for major intersections by using the Synchro traffic analysis and simulation program.6 The model set consists of two weekday AM and PM, and one Saturday midday peak-hour models, with scenarios under existing conditions or various proposed improvement alternatives.

Figure 9 shows weekday AM and PM peak-hour capacity analyses for major intersections in the corridor, under existing conditions. The graphic includes a table of intersection level-of-service (LOS) criteria based on average intersection control delay defined by the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM).7 LOS is a qualitative measure used to relate the quality of traffic service. The HCM defines LOS—using a qualitative scale from “A” to “F”—for signalized and unsignalized intersections as a function of the average vehicle control delay. For the intersections in a metropolitan urban area, LOS C or better is considered desirable; LOS E or better is considered acceptable; and LOS F is considered undesirable.

Overall, staff estimate that all the major intersections generally operate at a desirable LOS C or better in both peak AM and PM hours, except the intersection of Summer Street at North Street and the Route 3A Rotary.

Staff estimate that the North Street intersection operates at LOS D in the AM peak hour with an average delay of about half a minute per vehicle. The westbound approach is critical to the intersection, where more than 250 left-turning vehicles need to share the inside lane with through traffic. Staff estimate that the approach operates at LOS D, with an average delay of about 50 seconds.

Staff estimate that the Route 3A rotary operates at LOS E in the AM peak hour, with an average delay of 45 seconds per vehicle.8 The northbound approach is critical to the intersection, where one single lane carries heavy, primarily left-turning, commuter traffic. Staff estimate that this approach operates at LOS F, with an average delay of about one-and-a-half minutes.

The two intersections’ existing weekday operations are considered acceptable for their urban settings. Signal timings and lane assignments at all the signalized intersections appear to be appropriate under existing roadway layouts. Appendices B and C contain Synchro capacity analysis reports of the major intersections, including input volumes, signal timings, estimated delays and queue lengths, and LOS for AM and PM peak-hour existing conditions.

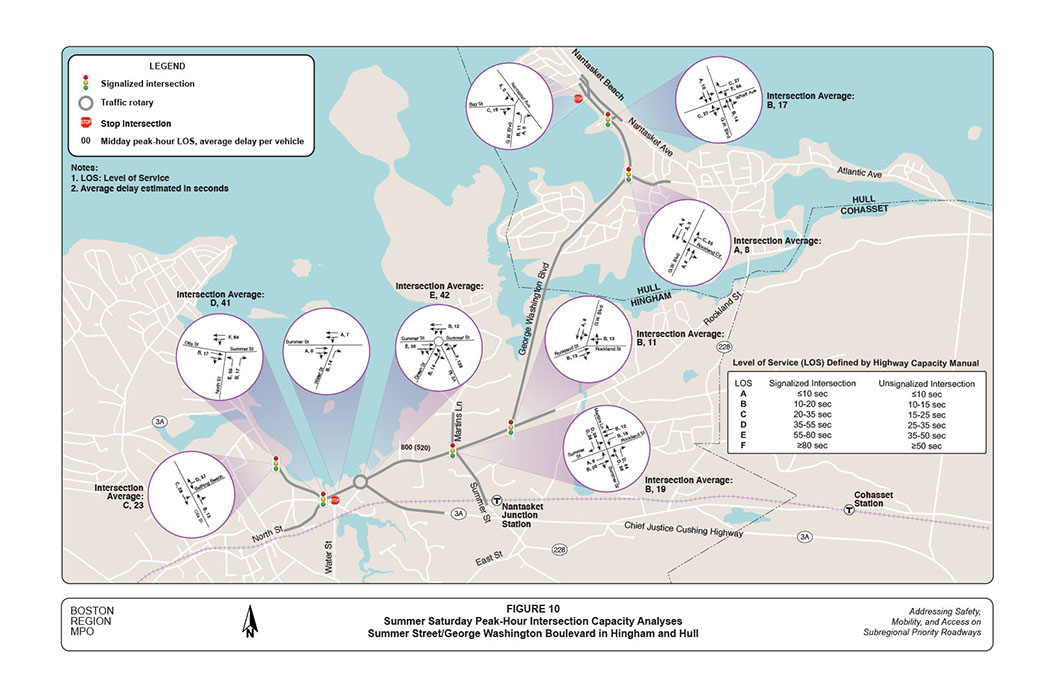

Figure 10 shows the Saturday midday peak-hour capacity analyses for major intersections in the corridor, under existing conditions. The analyses include an additional location per Hingham’s request: Route 3A (Otis Street) at Bathing Beach Driveway. This intersection is the main access to the beach’s parking lot, where the popular Hingham Farmers Market is held every Saturday from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM.

Although Saturday traffic volumes increase significantly from normal weekdays, the intersections’ operations maintain about the same or slightly worse LOS compared to the weekdays. The analyses indicate that most intersections operate at desirable LOS C or better, including the intersection of Route 3A at Bathing Beach Driveway. Appendix D contains Synchro capacity analysis reports of the major intersections for the Saturday midday existing conditions.

Staff estimate that the North Street intersection operates at LOS D in the midday peak hour with an average delay of about 40 seconds per vehicle; and that the critical westbound approach deteriorates to LOS F, with an average delay of nearly one-and-a-half minutes. The Route 3A rotary operates at LOS E, with an average delay of nearly 45 seconds per vehicle, and maintains the same LOS as the weekday AM peak hour. However, staff estimate that the average delay on the northbound approach increases to nearly two minutes; this is because, under existing rotary traffic operations, the heavy eastbound traffic (toward Nantasket Beach) consistently blocks the approach.

The area’s residents are very concerned about the high travel speeds in the corridor. In order to understand these fast driving patterns, MPO staff requested MassDOT to help collect spot speeds during the period when automatic traffic counts were being conducted in June and July 2015.

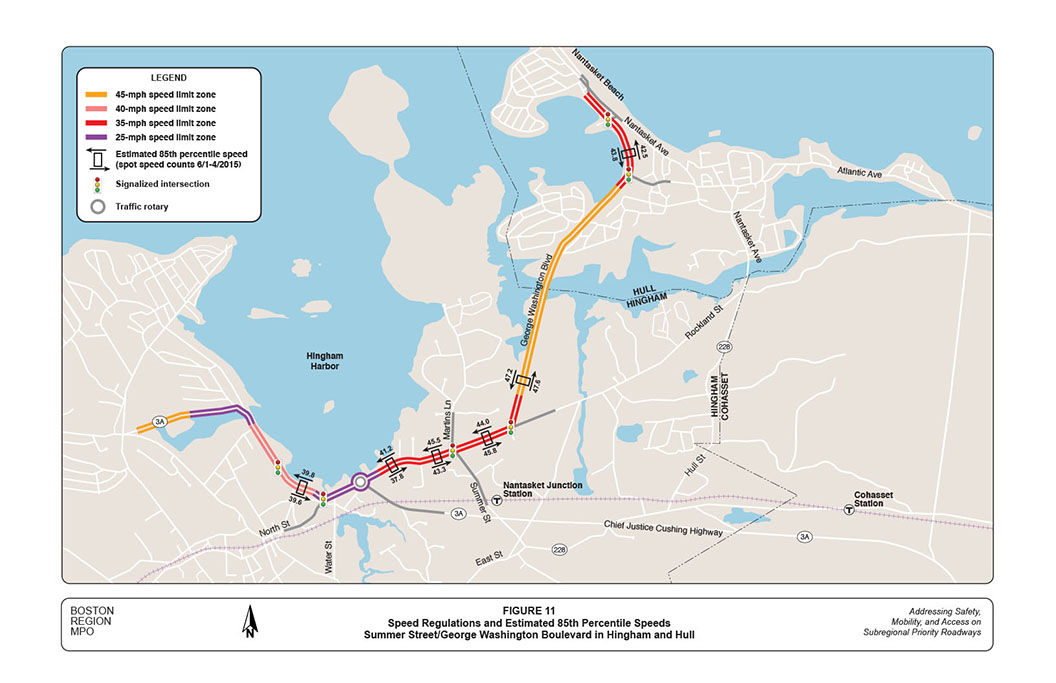

Figure 10 shows the existing speed regulations and estimated 85th percentile at selected locations in the corridor based on speed data collected on weekdays in the early June.9 The “85th percentile” is the speed at or below which 85 percent of vehicles passing a given point are traveling, and is the principal value used to establish speed controls.

Currently, regulated travel speeds in the corridor are: 40 miles per hour (MPH) in the Bathing Beach area; 25 MPH in Hingham Harbor and the Route 3A rotary; 35 MPH on Summer Street and Rockland Street in the Hingham residential area; 45 MPH on George Washington Boulevard north of Rockland Street until south of Rockland Circle; and 35 MPH on George Washington Boulevard in the Nantasket Beach area from Rockland Circle to Nantasket Avenue.

In the Hingham residential area’s 35-MPH zone, the estimated 85th percentile speeds are generally 8-to-10 MPH higher than the regulated speed, which confirms Hingham residents’ concern. In the 35-MPH zone near Nantasket Beach, the 85th percentile speed also is between 8-to-10 MPH higher than the regulated speed. The prevailing traffic speed of 43-to-45 MPH presents unsafe conditions for pedestrians to cross the street and for cyclists to ride with traffic.

During the study (after the speed data had been collected), Hull raised the concern of high vehicle speeds on George Washington Boulevard in the Rockaway neighborhood, which is located in the middle of a 45-MPH zone. Judging from the magnitude of speed increases, and according to the Hull Police Department’s observations, vehicles probably travel much more than 50 MPH in this 45-MPH zone.

Crash data are an essential source for identifying safety and operational problems in a study area. Analyzing crash locations, collision types, time-of-day, roadway conditions, and other factors also help to develop improvement strategies. For this study, staff collected two datasets:

Staff used the five-year MassDOT data to examine crash locations and crash rates. It used the police crash reports to construct collision diagrams to analyze safety and operational problems at the major intersections and in different segments of the corridor.

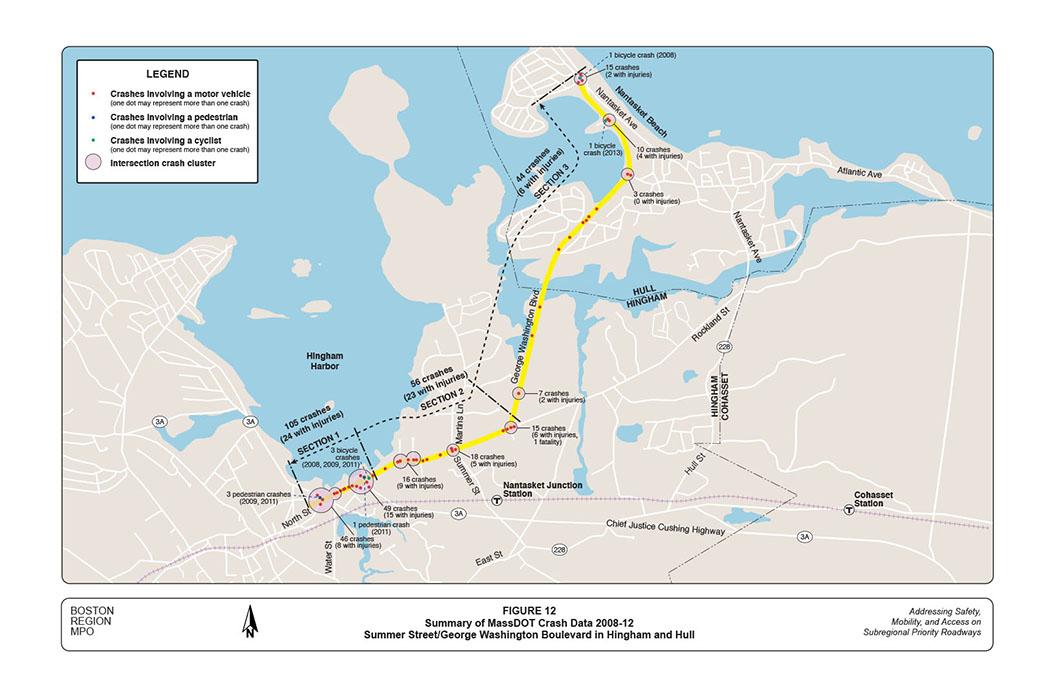

Figure 12 shows the crash locations and quantities for the five-year period 2008–12. The corridor is divided into three sections, each with similar land use characteristics:

Among the total 205 crashes, more than half (105 crashes) occurred in Section 1, which carried heavy traffic with frequent turning movements to and from adjacent developments; 56 crashes occurred in Section 2; and 44 crashes occurred in Section 3. Based on recent traffic counts, staff estimated the crash rates for the three sections:

The crash rate for Section 1 is much higher than the Massachusetts average for urban principal arterials (3.35 crashes per MVMT). The crash rates for Sections 2 and 3 are lower than the state average for urban minor arterials (3.74 crashes per MVMT). See Appendix E for worksheets.

Staff estimated the crash rates at major intersections of the corridor, as summarized below:

Appendix F contains worksheets for these crash rates. Appendix G summarizes the 2008–12 MassDOT crash data at each of the major intersections according to crash severity (property damage only, non-fatal injury, fatality, unknown), collision type (single-vehicle, rear-end, angle, sideswipe, head-on, rear-to-rear, unknown), pedestrian or bicycle involvement, time of day, pavement conditions, and light conditions.

Figure 12 shows the pedestrian and bicycle crash locations in the corridor that were identified from both datasets—in total, four pedestrian crashes and five bicycle crashes: 10

Significantly, these crashes all occurred on roadways adjacent to the pedestrian and cyclist areas of Hingham Harbor and Nantasket Beach.

To investigate safety and operational problems further, MPO staff constructed collision diagrams for the entire corridor by major intersections and in-between roadway segments, based on recent five-year crash reports provided by the towns’ police departments. The crash reports contain detailed information about how and where those crashes occurred. Appendix H presents the collision diagrams for different locations in the corridor.

Below we summarize major findings from the collision diagrams and other factors affecting safety and operations:

Based on the above analyses, MPO staff developed a series of short- and long-term improvements to address safety and operational problems. It is possible to implement the short-term improvements within two years at relatively low cost. Long-term improvements generally are more complicated and cover larger areas, which would require intensive planning, design, and funding.

As the corridor covers an extensive length of roadways with different land use characteristics, we describe the proposed improvements in four sections below.

Table 1-1 summarizes the proposed short- and long-term improvements for the section of Summer Street in the Hingham Harbor area, along with the area’s issues and concerns; these are arranged according to general roadway section, and by specific location, from west to east.

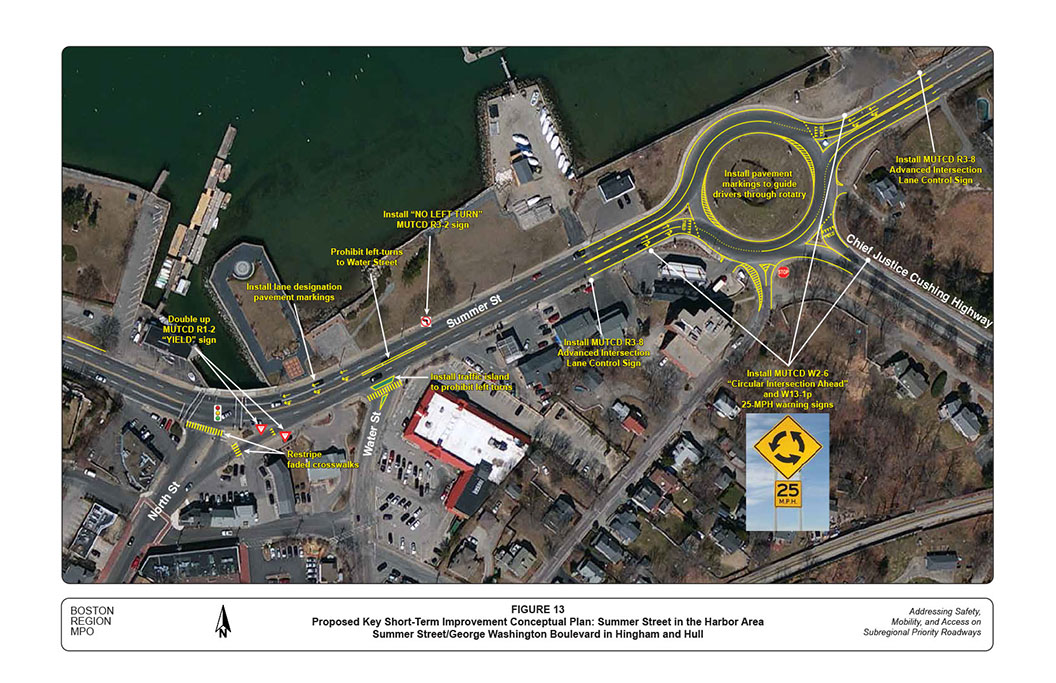

Figure 13 shows locations and layouts of the proposed short-term improvements in this section, including:

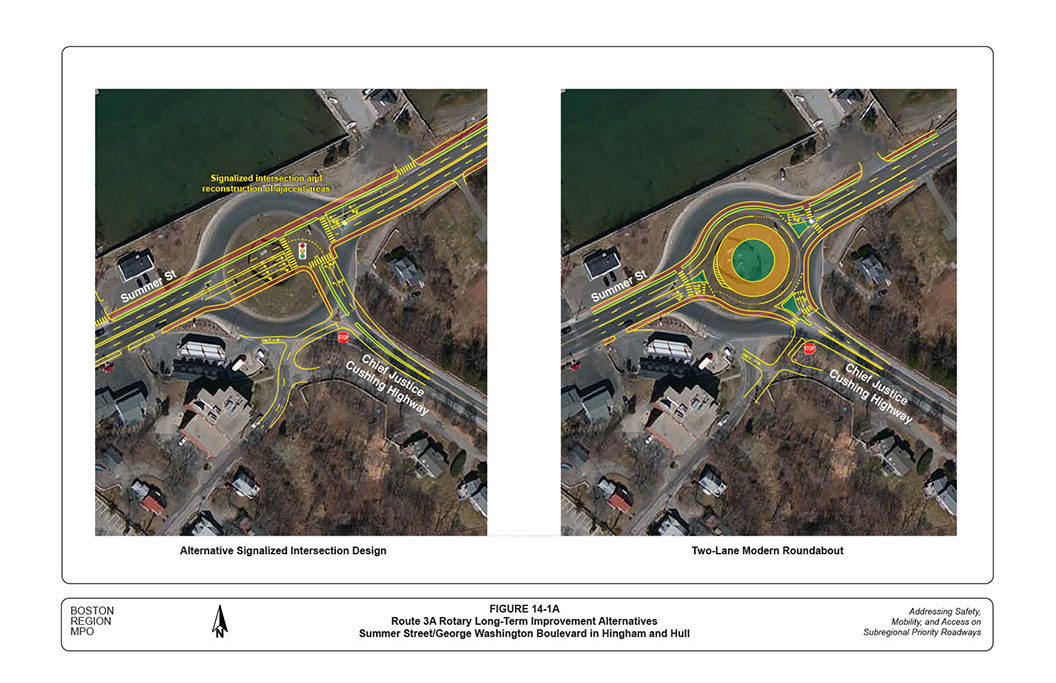

Figure 14-1 shows locations and layouts of the proposed long-term improvements in this section. Staff did not create the conceptual plan to scale, but in approximate proportion, in order to show how the proposed improvements would relate to their surroundings. The upper graphic of Figure 15 shows the proposed roadway cross-section. Major long-term improvements proposed for this section include:

MPO staff proposed to convert the rotary mainly based on safety concerns. It has a high crash rate and its wide layout is difficult and unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists to traverse. Although the rotary currently operates at LOS E or better during peak hours, drivers on the Chief Justice Highway approach endure excessive delays on weekday morning and summer Saturday midday peak hours.

Staff evaluated both the traffic signal and modern roundabout options. The traffic signal option was studied in two variations: one with a driveway to access Lincoln Maritime Center, and one without the driveway. The roundabout option was examined in single- and double-lane layouts. The single-lane layout was not feasible as its operation would fail during all the peak hours on weekdays and summer weekend days. Staff consider the signal option somewhat more favorable than the roundabout option because it has a smaller layout and would be safer for pedestrians and cyclists.

As shown in Figure 14-1, the proposed traffic signal option would incorporate the driveway to Lincoln Maritime Center. The intersection would operate at desirable LOS C or better during peak hours, with exclusive pedestrian signal phases. Staff also suggest that, at the functional design stage for the rotary conversion, the other signal option (without the driveway connection) and the two-lane roundabout option should be included for further examination.

Figure 14-1A shows conceptual plans for the two additional options. The signal option without the driveway would have a smaller layout with shorter pedestrian crossing distances than the one with the driveway. The Lincoln Maritime Center driveway needs to remain at its existing location so would disturb traffic operations at the intersection.

The two-lane roundabout option would require an inscribed circle (150-foot diameter minimum, 160-foot as shown) with two entry lanes from all approaches. Traffic operation on the Chief Justice Cushing Highway approach would improve to LOS E. With this option, the estimated average delay per vehicle would be slightly higher (about five seconds) than the proposed signalization. In the meantime, pedestrians need to cross two lanes of constantly moving traffic during peak hours.

At the intersection of Summer Street at North Street, crosswalks exist across Summer Street from both sides of North Street. However, the east-side crosswalk is used less often because of inconvenient and unsafe pedestrian accommodations on the east side of North Street.14 Staff propose to reconstruct the intersection by removing the right-turn channelization and reconfiguring the northbound approach with separate turning lanes, in order to slow down traffic and provide better and safer pedestrian accommodations. The reconstruction also includes upgrading the signal system with new mast arms and better traffic signal indications, relocating the signal control cabinet, increasing pedestrian staging areas and crosswalk widths (15-feet wide is desirable), and providing count-down and accessible pedestrian signals.

One essential long-term improvement proposed for this section is to reconstruct the harbor-side sidewalks as multi-use trails between the two major intersections. The Town of Hingham has improved many attractions in the harbor area, including Bathing Beach, Bandstand, Iron Horse Park, and Whitney Wharf Park. The proposed multi-use trail would serve as a foundation to connect all of these attractions. If the right-of-way (ROW) is available, it should extend from Bathing Beach (or even from the Crow Point neighborhood) to Steamboat Wharf.15Pedestrian access to Hingham Harbor would improve significantly by reconstructing these two major intersections.

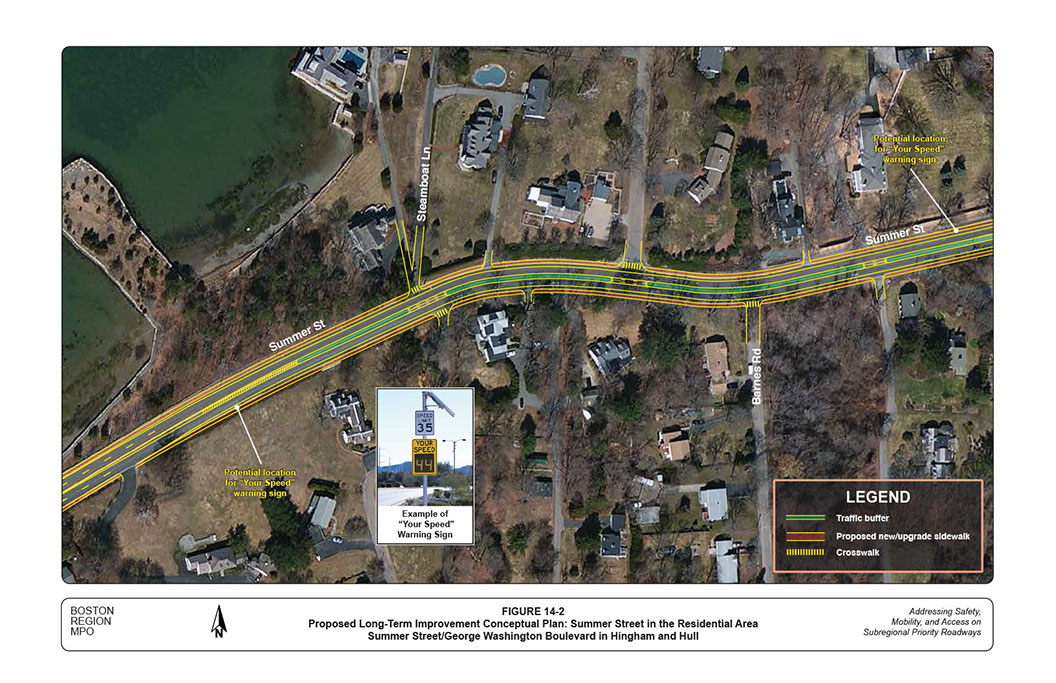

Table 1-2 summarizes the proposed short- and long-term improvements for the section of Summer Street in the Hingham residential area, with issues and concerns listed for reference. The key proposed short-term improvements include:

Figure 14-2 shows the conceptual plan of proposed long-term improvements in this section. The lower graphic of Figure 15-1 shows the proposed roadway cross-section accordingly. Major long-term improvements proposed for this section include:

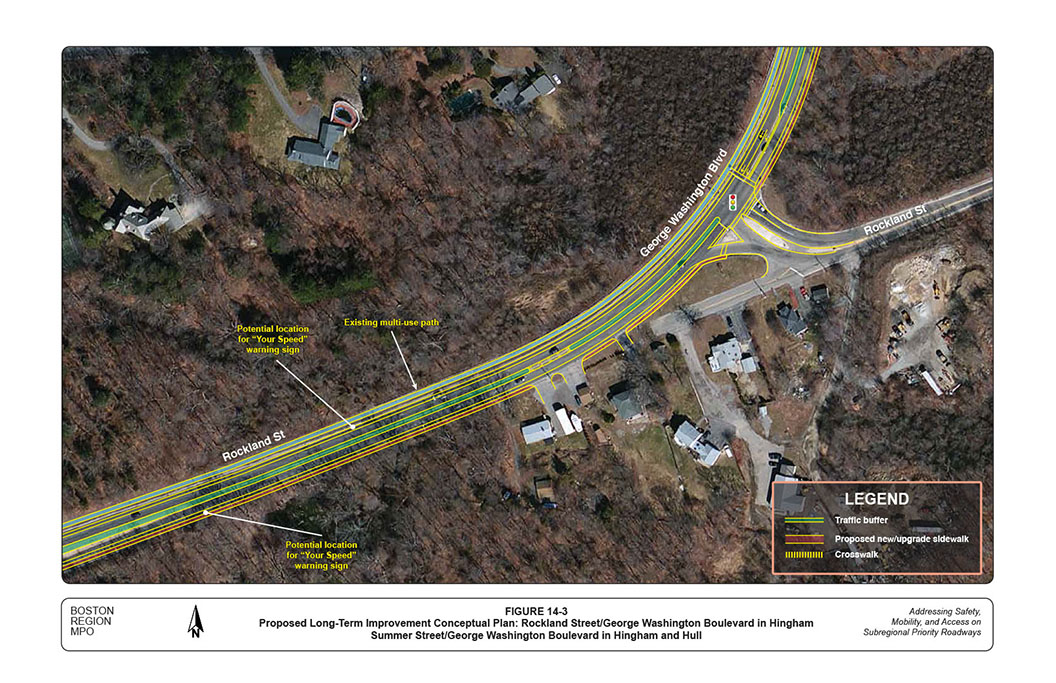

Table 1-3 summarizes the proposed short- and long-term improvements for the section of Rockland Street and George Washington Street in Hingham. The key proposed short-term improvements include:

Figure 14-3 shows the conceptual plan of proposed long-term improvements in this section. The upper graphic of Figure 15-2 shows the proposed roadway cross-section. Major long-term improvements proposed for this section include:

Table 1-4 summarizes the proposed short- and long-term improvements for the section of George Washington Street in Hull. The key proposed short-term improvements include:

Figure 14-4 shows the conceptual plan of proposed long-term improvements in this section. The lower graphic of Figure 15-2 shows the proposed roadway cross-section. Major long-term improvements proposed for this section include:

One long-term improvement alternative worthy of consideration is to extend the proposed multi-use trails from the Hingham Harbor area to cover the entire corridor until the Nantasket Beach area. The continuous multi-use path would be about three miles long and mostly on the scenic coastal side.

Figures 16-1 and 16-2 show the proposed roadway cross-sections for the four different sections of the corridor. The curb-to-curb roadway configurations would remain the same as those proposed in the above four sections. The proposed multi-use trails would mostly be 12-foot wide, except some ROW limited areas (10-foot wide minimum).

A quick review of the highway layouts shows that most of the proposed multi-use trails would be within the MassDOT’s right-of-way. The proposed reconstruction might require some land takings but most would be on public lands. As proposed previously, Hingham should at least consider the multi-use trails for the harbor section. If the right-of-way is unobtainable for some sections, a combination of trials, bicycle lanes, and sidewalks with carefully designed connections (such as crosswalks at intersections) could be considered.

Hull is concerned with traffic congestion in the Nantasket Beach area during the summer; the proposed bicycle accommodations in the corridor potentially would mitigate some of the congestion.

The MBTA Greenbush commuter line allows bicycles on most trains on weekdays and on all trains on Saturdays and Sundays. People can take their bicycles from the Nantasket Junction station and connect with the proposed bicycle lanes or multi-use trails all the way to Nantasket Beach. The parking at Nantasket Junction is underused, especially on weekends. Once the dedicated bicycle accommodation is available, a reduced fee or even free parking could be considered in order to promote cycling, instead of driving, to Nantasket Beach.

The MBTA will receive funding from Federal Transit Administration MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act) Passenger Ferry Grant Program to replace a twin engine and control equipment for the Quincy-Hull-Boston “Lightening” high-speed ferry (about $900K), and to upgrade the Pemberton Pier ferry terminal in Hull (about $200K). This funding would improve the Hull ferry service and would help to encourage use of the ferry to Nantasket Beach (via connection with MBTA Bus 714).

Further steps to mitigate congestion in the beach area and to increase transit usage include:

The most significant long-term improvement recommendation in the roadway corridor, except in the Hingham Harbor section, is the reconfiguration from four to two lanes plus a center lane as traffic median, or for left turns, and bicycle lanes on both sides. Such four- to three-lane road-diet applications have been applied in a number of US cities with positive results in improving safety for all modes of travel. The analyses in this section indicate that the proposed long-term improvements, including the road-diet section, would operate adequately under the future-year traffic conditions.

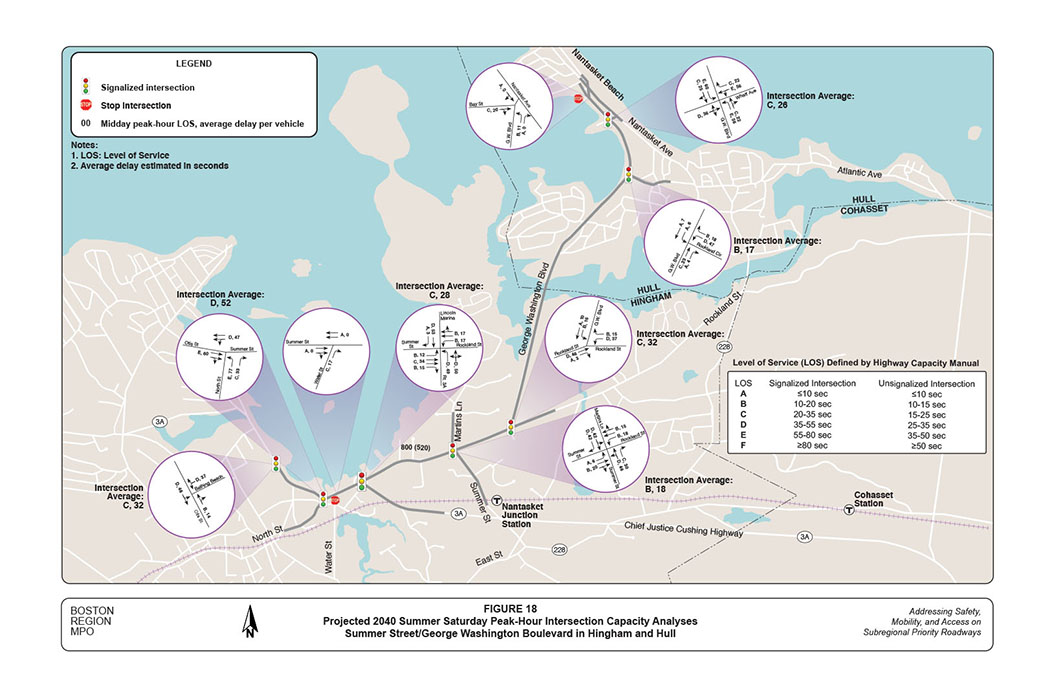

Similar to the base-year models, staff constructed future-year 2040 traffic models for the entire corridor based on the roadway layouts with the proposed long-term improvements. Staff also conducted future-year traffic analyses based on traffic growth projections from the transportation planning model recently developed for the MPO’s Long-Range Transportation Plan.20

Recent counts indicate that all sections of the corridor (except the Harbor section) experience average daily traffic of fewer than 20,000 vehicles. These sections are suitable for the road-diet application. Although in a few sections, such as Summer Street and Rockland Street in the residential area, traffic surges to more than 25,000 vehicles per day on some summer Saturdays and Sundays, these represent about 10-to-15 days per year and usually are not considered for roadway design.

Traffic simulations from the 2040 Saturday traffic model show that traffic would move constantly in the corridor without spillbacks from one intersection to another. The proposed three-lane configuration would remove left-turning vehicles from the main travel lane, and would widen appropriately at major intersections to include left- and right-turn lanes (and in some cases an additional through lane). Consequently, traffic would be able to continue moving on the main lane and pass through the intersections with no extensive delays.

Figures 17 and 18 show the intersection capacity of major intersections in the corridor under the projected 2040 traffic conditions for the weekday peak hours and summer Saturday midday peak hour. With the proposed long-term improvements, all intersections would operate at desirable LOS C or better during the weekday peak hours and at acceptable LOS D or better during the summer Saturday peak. Synchro capacity analysis reports of the major intersections for the future-year weekday AM, weekday PM, and summer Saturday midday peak hour conditions are included in Appendices I, J, and K.

This study performed a series of safety and operations analyses, identified safety and operational problems, and proposed a number of short- and long-term improvements to address identified problems in the study corridor.

The recommended key short-term improvements include:

These improvements could enhance safety for all users and improve traffic operations moderately. The recommended improvements at the rotary are more involved and more costly, but potentially could reduce crashes in the rotary and vicinity. With a high benefit/cost ratio, these short-term improvements should be implemented as soon as the resources are available from highway maintenance or local Chapter 90 funding.

Together, the conceptual plans and suggested long-term improvements create a vision that would accommodate all users and would improve their safety, mobility, and access in the corridor significantly. Some expected benefits from proposed long-term improvements include:

In addition, the corridor would benefit by promoting transit usage in the summer time and gaining a comprehensive parking and access management program at Nantasket Beach.

Implementing the proposed long-term improvements would require sufficient resources. MPO staff recommend the improvements be implemented in the following stages:

At this preliminary planning stage, staff estimate reconstruction of the entire corridor would cost approximately $12,500,000 to $15,000,000.21 The approximate costs of the three implementation stages are:

This study provides a vision for the corridor’s long-term development, and confirms that the corridor has great potential to operate safely and efficiently for all users and various transportation modes. It will require significant effort and collaboration on the part of all stakeholders, including the Towns of Hingham and Hull, residents and owners of adjacent developments, MassDOT, MBTA and DCR to achieve the vision.

The implementation process must ensure that all parties concur about how the recommendations can be realized in a resourceful and fiscally responsible manner. The Towns need to work with MassDOT’s Highway Division District 5 to initiate the project, obtain favorable review from MassDOT’s Project Review Committee, and identify potential funding resources through MassDOT and the Boston Region MPO.

Appendix L details the actions that are required in the various steps of MassDOT’s project development process, including a schematic timetable. Information regarding the project development process also may be found on MassDOT’s website, at www.massdot.state.ma.us/planning/Main/PlanningProcess/ProjectDevelopmentProcess.aspx and at www.massdot.state.ma.us/Portals/8/docs/designGuide/CH_2_a.pdf.

CW/cw

TABLE 1-1

Proposed Improvements: Summer Street in the Harbor Area

Location |

Issues/Concerns |

Short-Term Improvements |

Long-Term Improvements |

The section in general |

|

|

|

Intersections: Summer Street at North Street and at Water Street |

|

|

|

Route 3A Traffic Rotary: Summer Street at Chief Justice Cushing Highway/Green Street |

|

|

|

Route 3A (Otis Street) at Bathing Beach Driveway |

|

|

|

Route 3A (Otis Street) at Ship Street |

|

|

|

MPH: Miles per hour. MUTCD: Manual on Uniform Traffic Devices, Federal Highway Administration, 2009 Edition with Numbers 1 and 2 Revisions, May 2012. N/A: Not available or applicable.

TABLE 1-2

Proposed Improvements: Summer Street in the Residential Area

Location |

Issues/Concerns |

Short-Term Improvements |

Long-Term Improvements |

The section in general |

|

|

|

Signalized Intersection: Summer Street at Rockland Street/Martins Lane |

|

|

|

MPH: Miles per hour. MUTCD: Manual on Uniform Traffic Devices, Federal Highway Administration, 2009 Edition with Numbers 1 and 2 Revisions, May 2012.

TABLE 1-3

Proposed Improvements: Rockland Street/George Washington Boulevard in Hingham

Location |

Issues/Concerns |

Short-Term Improvements |

Long-Term Improvements |

The section in general |

|

|

|

Signalized Intersection: Rockland Street at George Washington Boulevard |

|

|

|

MPH: Miles per hour.

TABLE 1-4

Proposed Improvements: George Washington Boulevard in Hull

Location |

Issues/Concerns |

Short-Term Improvements |

Long-Term Improvements |

The section in general |

|

|

|

Unsignalized Intersection: George Washington Boulevard at Barnstable Road/Logan Avenue |

|

|

|

Signalized Intersection: George Washington Boulevard at Rockland Circle |

|

|

|

Signalized Intersection: George Washington Boulevard at Wharf Avenue |

|

|

|

Unsignalized Intersection: George Washington Boulevard at Nantasket Avenue/Bay Street |

|

|

|

MPH: Miles per hour. MUTCD: Manual on Uniform Traffic Devices, Federal Highway Administration, 2009 Edition with Numbers 1 and 2 Revisions, May 2012. N/A: Not available or applicable.

1 Details of the criteria and rating system may be found in the CTPS technical memorandum “Selection of Study Location: FFY 2015 Addressing Safety, Mobility, and Access on Subregional Priority Roadways,” April 2, 2015.

2 According to Smart Growth America, a “complete street” is a street for everyone. Complete streets are designed and operated to enable safe access for all users, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities. They make it easy to cross the street, walk to shops, and bicycle to work.

3 The estimation based on MBTA 2015 bus summer schedules from June 27 to September 4.

4 The estimation based on MBTA commuter ferry schedules effective May 25, 2015.

5 The trial was built about 20 years ago. Based on today’s standards, a two-way multi-use trail should be at least ten-feet wide.

6 Synchro Version 8.0 was used for the analyses. This software is developed and distributed by Trafficware Ltd. It can perform capacity analysis and traffic simulation (when combined with SimTraffic) for an individual intersection or a series of intersections in a roadway network.

7 HCM 2010, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington D. C.

8 The rotary is considered an unsignalized intersection.

9 Because of limited resources, the July speed data were collected for fewer locations. Although the traffic volumes are higher in the summer weekend, the observed 85th percentile speeds are about the same or slightly lower than the weekday average.

10 In this study, the term “pedestrian crashes” refers to those that involve at least one vehicle and one pedestrian; “bicycle crashes” refers to crashes that involve at least one vehicle and one bicycle. No crashes between at least one bicycle and one pedestrian were identified in the available data.

11 The retrofit would be accomplished through pavement markings under the existing rotary layout in order to save the high cost of reconstruction. The width of the traffic island on the Chief Justice Cushing Highway approach would need to be reduced slightly in order to allow two circulating lanes.

12 Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, 2009 Edition with Revisions 1 and 2, Federal Highway Administration, US Department of Transportation, May 2012.

13 Most of the left turns presumably are cut-through traffic heading to Hingham Square or further southeast. If access to the nearby supermarket is a concern, at least the turns should be prohibited during the AM peak period from 7:00 to 9:00. Meanwhile, the prohibition would require readjusting the signal timing at North Street and continuing to monitor traffic conditions at the Summer Street/North Street intersection (and the North Street/Mill Street intersection).

14 The east side of North Street also is more convenient for pedestrians from Hingham Depot and the Hingham downtown area.

15 Based on town’ assessor’s maps, the proposed multi-use trials in the Harbor area would extend slightly beyond the MassDOT Route 3A right-of-way and may require some land takings. Most of the adjacent lands are owned by the town, except Kimball’s Wharf (Hingham Harbor Marina) and the nearby small office building.

16 The bicycle lanes also can be used as roadway shoulders for emergency stopping.

17 Field observations in July 2015 indicated that the two remote parking lots were underutilized, even during high summer.

18 Currently, Bus 714 provides nine trips each direction on summer Saturdays and Sundays. It can be increased to 15 trips in conjunction with the existing Bus 220 schedule. No summer Saturday or Sunday ridership data are available. The data collected in the winter of 2013 show a relatively low ridership of about 50-to-60 riders on all trips on an average Saturday.

19 The Town of Hull conducted a study with a service plan of the summer ferry from Boston to Steamboat Wharf in 2009 and received support from the Boston Region MPO’s Subregional Mobility Program. The further study can be based on the previous study.

20 The model predicts future traffic growths base on demographic changes from 2015 to 2040. As population and employment are predicted to increase slightly in Hingham, and practically not at all in Hull, traffic growth at various locations in the corridor is projected to increase by 5 percent or less. Therefore, staff therefore used 5 percent traffic growth for all 2040 weekday and Saturday peak-hour models.

21 This cost was estimated using the general expenses of similar projects. The estimate is only for design and construction and does not include right-of-way, utility relocation, or other contingency costs.

22 This estimate does not include relocating major gas lines at the middle of the Route 3A Rotary.